Talkin’ about Talking

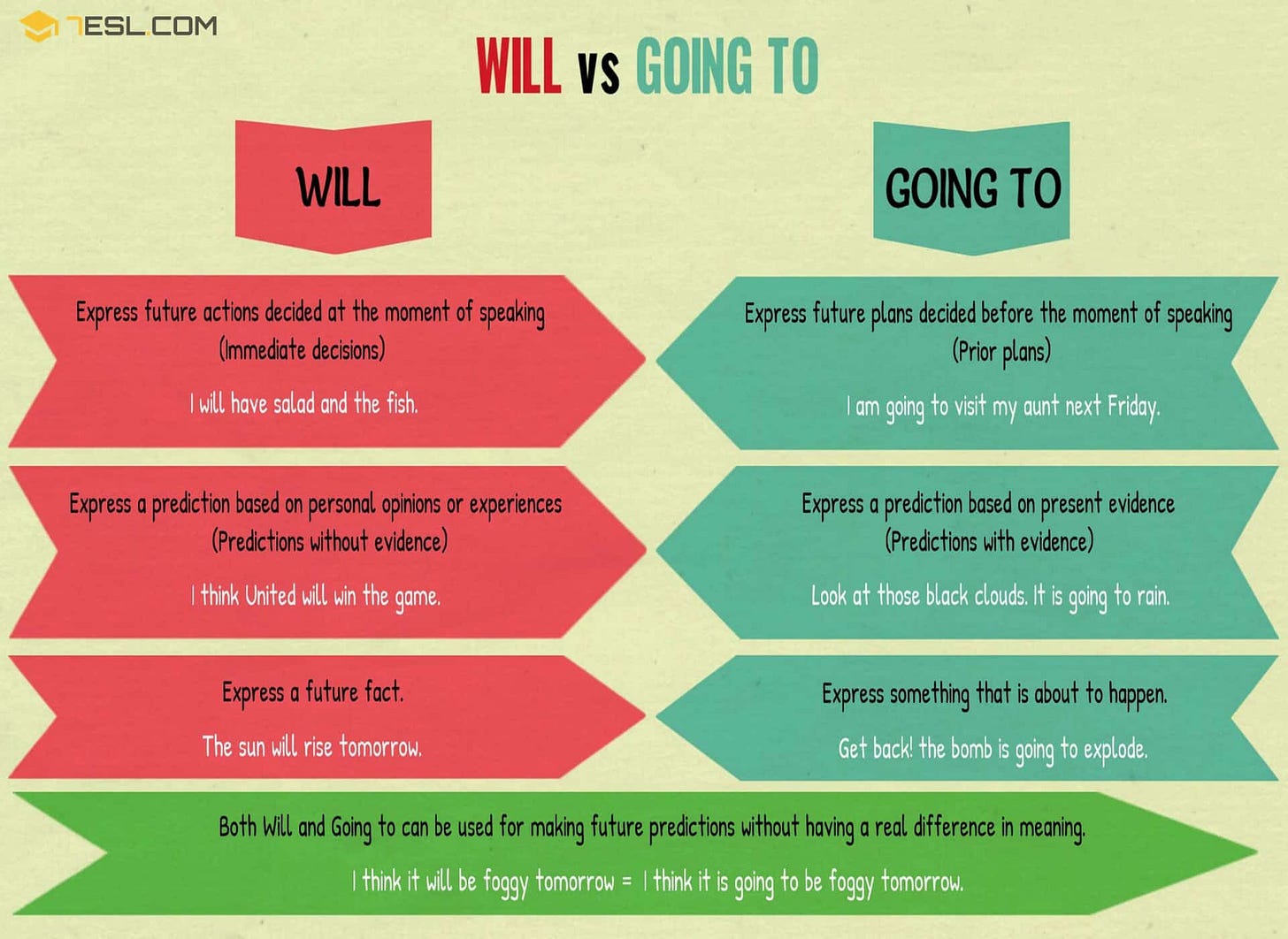

One of the world’s great ironies is that native speakers can't explain the rules of their own language. We speak intuitively, meaning we don’t know the “why” or “what,” behind our speech. Quick one for your native English speakers: what’s the difference between “will” and “is going to” as future tense signifiers? Here’s an English-second-language source on the matter:

I’ve seen a few sources delineate the two future tenses in this manner, though it doesn’t quite feel right. I’ve said “going to” (or “gonna”) for actions decided at the moment of speaking, and I’ve expressed prior plans with a “will.” In my experience, a “will” just feels more emphatic than a “going to.” The article that I will write has a higher probability of appearing than the one that I am going to write.

That’s just a hair-splitting grammar question. It’s even more interesting that people don’t know what sounds come out of their own mouths. If you’re a native English speaker, say the two words below. In each case, keep one hand in front of your mouth and another on your throat:

Beach

Peach

You’ll notice two differences between the leading consonants. First, the opening sound of “beach” is voiced, meaning it involves a vibration of your voice box. You should feel a bit of action in your upper neck. Second, the opening sound of “peach” is aspirated, meaning you spit out a burst of air. You should feel this on the hand in front of your mouth. Now, try this word:

Speech

Pay attention to that “p.” Sound. You’ll notice the “p” sound has a voice box vibration but lacks an aspiration. In other words, it’s a “b.” It’s not surprising to see a “b” here, as we often see consonants become voiced when they sit in front of a vowel.

Some write words like reading or talking as readin’ or talkin’. That’s accurate, but it’s not accurate to present this as slang or some old-school cowboy riff-raffin’. If I eavesdropped on conversations at my local coffee shop, I would hear the in’ ending more frequently than the ing one. That’s a purely hypothetical example, of course. Furthermore, it’s not just for chit-chat among buddies. Pay attention to this in your next work meeting, and you’ll hear the same thing.

It’s worth noting, though, that the in’ orthography is a bit misleading. Outside of some parts of England, no one pronounces these words with a g sound. Instead, the ng represents a voiced velar nasal. In case you haven’t rigorously studied every article I’ve written about language (lame), I’ll break that down for you below. Or should I say “I’m gonna break that down for you below?” Not sure.

Voiced - vibrating the voice box.

Velar - The back of the tongue hits the back of the mouth.

Nasal - a consonant forcing sound through the nose. Hold your nose while making this sound, and you’ll feel a brief expansion of the nostrils. For best results, do it loudly in public.

Say a few strong “-ing”s and you might notice an issue. We articulate the vowel (/I/) in the top front of the mouth, whereas that voiced velar nasal (/ŋ/) sits at the back of the mouth. This involves a sudden backward jerk of the tongue. This causes a problem since we need that /Iŋ/ sound combo for the language’s common present tense. Thus, speakers sought efficiency. Let’s take the three pieces of our voiced velar nasal, and analyze how they function alongside its pair-bonded vowel. The “voiced” part isn’t an issue. All English vowels are voiced, so we find some symmetry there. The issue arises with the “velar” part of the consonant. We’d like to find a way to avoid that backward jerk of the mouth. We also want something that kind of sounds like the old ŋ. The “z” sound fits well with the /I/ vowel, but you’d probably confuse everyone if you went around saying “readiz.” In other words, we want a voiced nasal that sits a bit closer to the top and front of the mouth. We have one: “n.” Saying “in” (or, really, more like “ehn” or even “uhn”) avoids the tongue whiplash while maintaining a similar sound.

This change isn’t unusual. In fact, speakers across various Indo-European languages have been addressing the back-of-mouth-consonant versus front-of-mouth-vowel struggle since pre-historical times.

Getting Crabby

For the last couple of years, YouTube has relentlessly recommended a video titled “Why Do Things Keep Evolving Into Crabs?” It doesn’t what videos I’m watching. Economics, board games, sports, language. YouTube thinks I need to know about crabs. After a long and valiant battle, I must admit defeat. I watched the crab video. The basic idea is that various shrimp or lobster-like species evolve in a more rounded form to avoid predators and increase mobility. This has led to a series of “false crabs,” who look like normal crabs but don’t share their ancestry. This is an example of “convergent evolution,” where genetically unrelated species select for similar traits. In other words, it’s a lot like an unvoiced fricative pronounced at the front of the mouth. Let me explain.

The Indo-European language family began in the Russian steppes around 6,000 years ago. Over time, various migrations slowly overwhelmed the native populations of Europe, Iran, and North India, placing a large swath of the world under a single language family. Early migrations into Europe brought forth the ancestors of the Germanic, Italic, Celtic, and Greek languages. During these waves of emigration, the language spoken on the Russian steppes continued to change. One noticeable change involved certain “k” sounds shifting into “s” sounds. This allows scholars to separate the various Indo-European branches into “centum” or “satum” languages. “Centum” references the Latin word for “hundred.” “Satum” is the word for “hundred” found in the Avesta, the holy book of Zoroastrianism. If a language’s ancestors migrated before the change, that language kept the original “k.” These are the “centum” languages. Later migrations (the “satem” languages), reflect the new “s” sound. The Balto-Slavic and Aryan languages fit into the “satum” bucket, and some scholars also include Armenian and Albanian in this group. Check out the word for “hundred” in a few of them1.

Lithuanian: simtas

Czech: sto

Persian: sad

Hindi: sau

I think that clears up the “satum” part, but you might remain confused by the “centum” name. Some readers are probably saying “sentum, satum, sentum, satum” and wondering what the hell I’m talking about. Isn’t the “c” in centum pronounced just like the “s” in “satum?” I regret to inform you that the “s” sound you’re making with “centum” is, in fact, a false crab.

Alveolar Carcinization

Let’s clear that up right now: in Classical Latin, it was pronounced “kentum.” Latinate words make their way into English not from Classical Latin but from a Medieval version of French. By that point, some of the original “k” sounds in Latin had shifted. Some, but not all. You’ll notice that we hear an “s” in words like “civil,” “censor,” and yup, “cent.” Yet, we still hear the old-school “k” in equally Latinate words like “capital” or “capture.” Why the difference? First, remember that the initial vowels in words like “capital” would have sounded more like the vowel in “top.” Those vowels were closer to the back of the mouth. They were, in other words, closer to where the “k” is articulated. Meanwhile, the words “civil” and “cent” forced the speaker to combine a back-of-mouth consonant with a front-of-mouth vowel. This creates the same problem as the -ing issue from our first section. Speakers solved this by shifting the “k” sound to an “s” sound2 when doing so synergized with the subsequent vowel. Note that a similar process occurred with the “g” sound. Latin speakers pronounced the “g” in “Germanic” as we would in “get.”

That clears up part of the “centum” confusion, but you probably still have one open question. Isn’t the English word for “hundred” something like, I don’t know, “hundred?” Where’s the “k?”

Again, it used to be there. In the first century BC, the Germanic languages underwent a series of changes called “Grimm’s Law,” which I’ve discussed in previous articles. In short, all the “k” sounds in Proto-Germanic turned into “h” sounds, granting us a breathy “h” in “hundred.” Thus, we avoided the “k” issue in “centum” altogether. As tends to happen in life, though, fixing one problem creates others. In our case, many “g” sounds from Proto-Indo-European de-voiced into a “k.” In English, we haven’t resolved the associated inefficiencies. Other Germanic languages, however, have put in some work.

I don’t know what lead me to research Swedish pronunciation, but I’m glad I did. Consider this explainer from Tandem.

Consonants in Swedish

C = more of an “s” sound before e, i, and y, everywhere else it has a “k” sound

G = always a hard “g” like in the word get. However, before e, i, y, ä, or ö this letter sounds more like “y” (like yes)

K = “sh” before e, i, y, ä, ö. Before a, o, å, u, K = “k” (like kind)

Huh… does this sound familiar? Swedish settled on slightly different sounds (the referenced “sh” above is actually /ɕ/), but the shift otherwise matches the Latin one. The “k” sound moves forward before front-of-mouth vowels and stays before back-of-mouth ones.

Swedish isn’t alone. One might also notice that an English “k” often corresponds to a “ch” in German. Consider make & machen or cook & kochen. These “ch” sounds appeared as as part of the High German Consonant Shift, where various German stops shifted into fricatives or affricatives3. The same change explains the difference between “sleep” and “schlafen” as well as “water” and “Wasser.” The “k,” however, degraded in a more complicated manner.

Consider the phase ich auch, meaning “me too.” If you’re unfamiliar with German, you might assume that the two words sound similar. They do not. Although both “ch” sounds stem from an old Proto-Germanic “k,” that old “k” broke into two separate sounds. The latter sound, in auch, is fairly common among Indo-European languages. That’s the unvoiced velar fricative, written as /x/ in IPA. You still hear this in some parts of Scotland, in the throat-clearing sound at the end of “loch.” The one in “ich,” though, remains a bit more peculiar. This is the unvoiced palatal fricative, /ç/, better known as “the sound that shows everyone you’re a foreigner.” Note that the /x/ sound is pronounced in the same place as our “k” in make. In the words, the /k/→/x/ shift is just a stop from becoming a fricative. The /ç/ sound, however, came when /k/ both 1) morphed into a fricative and 2) moved toward the “palate” - the top and center of the mouth.

If you want to know whether to pronounce a “ch” as /ç/ or /x/, education resources often provide a list of vowels that you’ll forget within 30 seconds. The rule, though, looks much like the ones we’ve seen in Latin and Swedish. Back of the mouth? Keep the back-of-the-mouth /x/. Front of the mouth? That corresponds to /ç/; the sound that’s closer to the front. That’s why the word for daughter (Tochter), uses an /x/, while the one for daughters (Töchter), uses a /ç/.

In total, that’s four independent shifts of the same consonant, in the same way, across thousands of miles and thousands of years. Remember that, if you see two languages follow a similar pattern, it doesn’t necessitate a common ancestor. We all have the same tongues, palates, and throats. If we try to economize our speech, we’ll keep finding similar shortcuts. At least, until we evolve into crabs.

All are Romanized, with diacritics removed

With a “ts” intermediate phase.

Affricatives are stops immediately followed by fricatives. The most common English version is probably “ch” (“t” followed by “sh.”). In German, you see it mostly with “z,” which sounds like “ts.”

I always learn so much from your posts, Klaus! And your example of crab-like creatures reminds me of the time I was at an aquarium and noticed that from above, carp, penguins, and otters look the same. Convergent evolution among three phyla!

I for one can't wait to evolve into a crab.

Any plans to do an article on vowel length??