I Like Streamlined Versions of Existing Board Games

The next low-hanging fruit.

I just returned from Dice Tower West, so I want to talk about board games. I considered writing a generic article about my favorite games from the convention. After seeing similar posts on Facebook, I realized that nobody cares. Instead, I decided to highlight a commonality between two games that seem to share little in common.

I’ve complained about games taking up too much space or expecting players to finish the design. I’ve also grown less satisfied with games that require spreadsheet exercises upon their completion. I definitely don’t like the idea that quality means adding more and more and more. The best expansions either fix an aspect of the base game or add variety for frequent players. I don’t need three extra boards, nor do I need to collect a 15th resource.

I’m happy to see that I’m not alone in this pushback. No Pun Included, a board game commentary couple on YouTube, exemplified a frequent critique of the hit zoo-builder Ark Nova. They argued that the game’s massive deck (which you’ll find packed in three separate bags) made it difficult to execute a long-term strategy. Despite this issue, the game received so much acclaim that expansion seemed inevitable. No Pun Included ended their mixed review of the game with a Klaus-certified plea.

Here’s my challenge to the designers, developers, and publishers [for an expansion]. Maybe adding more isn’t what this game needs. Maybe re-tool this deck instead… I feel like this game is one more expansion away from being a game that we’ll remember for a very long time.

Well, Ark Nova announced its expansion… and it adds sea animals. It also adds additional actions, new bonus tiles, and asymmetrical player actions. Sorry, No Pun Included. You lost this round.

Michelangelo provided one of the great quotes in human history when he noted that the stone contained the completed sculpture and he just needed to remove the unnecessary bits. I like to imagine that the quote started as a 10-page essay that he whittled down into a one-liner. No Pun Included and I don’t seem alone on our Michelangeloan view of board gaming. Toward the end of the convention, the Dice Tower hosts provided a list of their pet peeves in gaming. Multiple participants expressed their annoyance at campaign games, where publishers pile on hundreds of hours of content that will never get touched. One of the speakers joked that designers don’t need to playtest the second half of a campaign game, since most of their customers will never experience it.

I need to clarify a couple of points before proceeding. First, I’m not arguing for miniature versions of games. I enjoy Tiny Epic Galaxies, mint tin games, and 13-card print-and-plays. That’s not what I’m talking about, though. Those boil down a mechanic or game to its most basic form, and that’s not quite the same task. After all, Michelangelo didn’t say he made the stone as basic as possible or removed its distinctive features. He removed the extraneous bits and unveiled the beauty underneath. Second, I also won’t argue that these games improve on spiritual predecessors. That’s a topic for another day. I just think that these experiences represent an archetype that more designers and publishers should pursue.

Aeon’s End —> Astro Knights

I tried Aeon’s End at the suggestion of a reader named James. I’m glad that I did! Since then, I’ve introduced it to multiple people at the local board game cafe and played its sequel, War Eternal, two separate times at the convention. It’s safe to say that I like Aeon’s End. Or, more accurately, I like playing Aeon’s End.

I’m shocked by how much discussion I see regarding setup and teardown. For example, I enjoy playing Caverna on the Board Game Arena. Yet, that laborious setup prevents me from ever pursuing a physical copy. The game features so many tiles and chits, and the setup can change dramatically among different player counts. Maybe I’m just a bit of a winner. The average gamer seems to stomach these issues and many hobbies require far more annoying undertakings. Still, I think we ought to consider the entire experience of playing a board game.

In Aeon’s End, players represent wizards trying to take down a boss. Each player starts with a hand and a deck with five cards in each. Most of these cards are generic, though a smaller number (usually 1 or 2) is specific to that character. All players may purchase additional cards from a common market. The common market contains 9 stacks of cards, delineated into three categories. Each stack contains 5-7 copies of the same card. Players usually need to choose between a combination of cheap and expensive cards, so that they’re able to take effective actions at both the beginning and end of the game. Each wizard needs health tokens to represent their life, alongside four square “breaches” that one must rotate to the appropriate orientation.

Next, the player prepares the boss. The boss will often require its own set of cards, tokens, and other components. After gathering those, one will have to construct the main deck for the boss. Each deck contains three “phases” worth of cards, with the phase 1 cards being the weakest and the phase 3 ones being the strongest. This deck consists of nine cards specific to that boss, alongside a general pool of cards that one must use for all bosses. Players sort the generic boss cards into three piles, one for each phase, with the number of cards in each pile varying based on the number of players. Then, boss-specific cards are mixed into the pile of the appropriate phase, before being stacked in order from least to greatest. Next, you just need to set aside the charge tokens (for the players) and the power tokens (for the boss). Finally, set the two health dials to their appropriate numbers. You’re now ready to go!

Welcome back, readers who skipped the last two paragraphs. Look, Aeon’s End is no Caverna, but that setup ain’t fun. It’s worse at a cafe or a convention, where the last player may not have returned cards to their correct locations.

Then there’s the part where you teach the game to new players. Luckily, Aeon’s End features pretty straightforward rules. As a former math tutor, though, I remain extra sensitive to anything related to teaching. Here, Aeon’s End errs in a couple of ways.

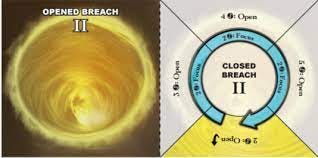

The first issue comes with the “breaches.” The breaches represent squares where players can prepare a spell, with spells being the primary way of damaging the boss. Players begin with a mixture of open and closed breaches. Naturally, one can prepare a spell on an open one. Less naturally, players can prepare a spell on a breach that has been “focused” on that turn. I’ve included a picture of a breach below for reference.

What does “focus” mean, you might ask? It means rotate. You rotate the breach. Yes, I know, the nice arrow-circle-thing says “focus” in it, but I oppose this sort of dissonance between gameplay and mechanics. The rulebook for Fantastic Factories begins by explaining that it uses the word “workers” to refer to “dice.” Man, if only we had a word for “dice.” Unless your game oozes with theme, just call the thing what it is. Besides, I don’t even think the term “rotate” distracts from the theme. We’ve all used doorknobs, so there’s an intuitive connection between rotating something and opening it.

The next teaching issue arises from gaining a “charge.” A “charge” is a player specific-ability-token. The player can spend this token at a later point to activate a powerful action. Each character can only activate the charge a set number of times in the game, as indicated by the number of charge spots on their player boards. I’ve always found myself explaining this multiple times. I can’t think of a fancy, thematic way of wording this, so I’d just say “player-specific ability token.” Keep it simple.

Finally, the boss decks contain three types of cards. The first two are straightforward: minions and attacks. The first represents an enemy you must defeat while the second consist of immediate effects. The third one, though, is a bit more interesting. These “Power” cards act like the attack ones, but they don’t actualize until a few turns have passed. The wording though is a bit awkward. What do you think the difference between “Power 2” and “Power 3” is? Most, I imagine, would assume that the latter is powerful. That’s not the case. Rather, the second activates after 3 turns, while the former activates after 2.

Yes, I did just spend multiple paragraphs nitpicking a small number of words and none of these rules are that complicated. Still, I think that board game hobby could use a bit more nitpickers. Everything would run more smoothly, especially for less hardcore audiences, if games faced this sort of feedback. Later in the convention, I played a game in the Alien universe. It required players to complete a variety of missions, one of which involved bringing a “motion sensor” to a certain room. One problem: the rulebook and player aid mention “motion trackers,” but no “mention sensors.” A huge deal? No, but edit your damn game!

Let’s get to point of this section: Astro Knights. It plays more-or-less like Aeon’s End, but consider these changes to the setup.

Each boss has its own deck, so you don’t need to mix boss-specific cards with general ones. The game also removes the three “phases” of cards. Instead, each time the boss runs out of cards, its phase increases. Later phases increase minion health and make certain cards more powerful. For example, a card may say “on Phase 3, increase damage dealt by 4.” This means the same card works for all phases. With these changes, players can grab the boss’s deck, shuffle it, and move on.

The “Power” cards no longer exist (at least for the boss I played). I only saw attacks and minions. Another small point of confusion is removed.

You don’t need to take any health tokens, charge tokens, or breaches for your character. The first is handled by a health bar, and the second mechanic has been altered. Now, you pay energy (aka money) to power up your special ability, and the ability activates once you reach maximum power. Remember the whole “focus a breach” thing? You can forget that too. Each player may pay three energy to buy an additional slot. That’s it.

Finally, there’s the store. You no longer create nine piles that each contain several copies of the same card. Instead, the game comes with 6 types of sore cards, and players may buy the top card in each stack. Setup, therefore, involves no decision-making. It’s the same 6 piles every time.

Let me repeat myself: I’m not arguing that Astro Knights replaces Aeon’s End. I like the breach system! I like the “Power 2” cards! The new deck store system (i.e., 6 heterogeneous piles rather than 9 homogenous ones) also makes the game a bit less strategic and a bit more tactical. You can’t craft a plan of which cards to buy before starting the game. I don’t know if the game is better, but I do think this was a better direction for the series. Fans could already buy a legacy version, a couple of sequels, and several expansions, Astro Knights represents the best next step the series could take. It had already taken the “add more stuff route” several times. Despite the streamlining, it’s not Tiny Epic Deck Builder nor My Little Aeon. The game feels like Aeon’s end on a turn-to-turn basis. It feels a lot less like Aeon’s End, though, when you’re setting up, tearing it down, and explaining a couple of the awkwardly worded rules.

Caverna/Agricola/A Feast for Odin —> Nusfjord

I wrote a whole article about worker placement games and I’m already at 2,000 words, so I’m going to spare everyone the details on these four games. Long story short, these games come from famed designer Uwe Rosenberg, and they all play as follows:

There are a bunch of spaces on the main board

You put a wooden thing in one of these spaces

When your wooden thing is in space, no one else can put their wooden thing there

When you put your wooden thing in one of these spaces, you:

Sometimes gets you a bunch of stuff

Sometimes gets you a thing that fills spots on your private board

Some spot-filling things help you get more resources

Some spot-filling things give you points at the end

Congrats, you are now an expert on the Uwe Rosenberg oeuvre. I like worker placement games, and he makes some of the best. The problem with this genre, as I mentioned in the article about it, is that players gain such a large advantage by conjuring extra workers. If you can complete three moves while your opponent only makes two, they’re going to have a hard time accomplishing a fraction of what you do. It’s why I called gaining workers the “wish for more wishes” of board gaming. Designers can counteract this in one of two ways. The first is kinda annoying, and the second highlights what I love about Nusfjord.

Option 1: Feed your workers

The game will require players to feed their workers. To do so, players will have to spend some number of resources per available worker. Upon failing to do, players will lose the worker or face some other penalty. This helps counteract the extra-worker advantage. Sure, you can take extra actions, but you lose some of the resources gained from these actions. This mechanism can, unfortunately, make much of the game feel like upkeep. Players spend their initial moves avoiding penalties instead of gaining bonuses.

From a mathematical standpoint, I understand that avoiding a loss is the same as gaining a benefit. It just doesn’t feel that way. I like when games make me feel powerful. Astro Knights and Aeon’s End work so well because you start by hitting the boss for one point of damage or buying a cheap item from the. An hour later, you’re dealing double-digit damage and or triggering your character’s unusual abilities. On the contrary, so many of these early Euro games make me feel like I’m struggling just to get started. Yes, the worker-feeding usually only challenges players for the first third to half of the game, but why should the game get to annoy me for its first third or half? This can also differ by skill level, of course. I understand that some of you score 700 points before you open Agricola’s box. For the rest of us, the “feed your workers” mechanic feels stifling.

Granted, games can also make it easy to feed your workers. I can’t imagine a player failing to feed his or her workers in A Feast for Odin unless they chose to do so for some strategic reason. This helps avoid the downsides of the mechanic, but I think there’s an even better way to approach this.

Option 2: You can’t gain more workers

The other option involves just… not having the option to gain workers. Two of my favorite theme-lite resource-conversion puzzles, Underwater Cities and Lost Ruins of Arnak, opt for this solution. Unlike his earlier games, Uwe Rosenberg’s Nusfjord does so as well. Players will place their workers a total of 21 times: 3 times per round over the course of 7 rounds.

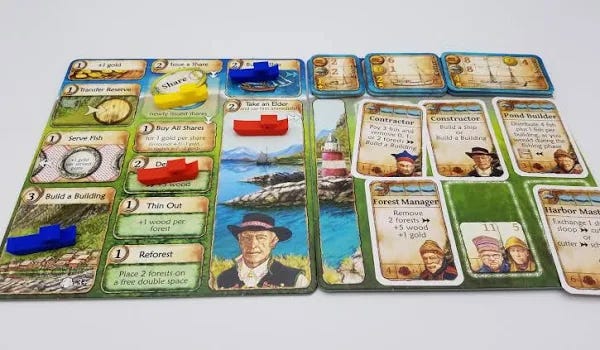

In fact, Nusfjord seems to streamline every aspect of the typical Rosenberg game. The game contains only three resources: wood, fish, and money. The board (shown below) contains a much smaller number of actions than you’ll see in other Rosenberg games. Players can obtain ships (which provide fish at the end of every round), elder cards (which provide an extra action space), or buildings (which provide a variety of buildings). These buildings come from the A, B, and C decks. The A deck contains buildings that work best in the early game, deck B contains buildings that work best in the mid-game, and deck C contains, I don’t know, take a guess.

A typical Rosenberg spatial puzzle fills each player’s personal board. This puzzle is simpler than the ones you’ll see in Agricola and Caverna, and it’s basically a preschool assignment compared to A Feast For Odin. Still, you will face some tradeoffs. The board contains 11 spaces, six of which will be covered by a forest to start the game.

Players can chop down a forest to gain wood, and wood helps you buy buildings and ships. Removing these forests reveals a pair of empty spaces, which deduce points at the end of the game. Yet, these empty spaces also provide spots for buildings, which can earn the player immediate benefits, recurring abilities, or extra victory points at the end of the game.

The game still contains a couple of counterintuitive parts. I won’t explain how the investment mechanic works, and I did have to re-read the rules about acquiring fish. Overall, though, it’s a quicker setup and teardown than any of the other worker-placement-tile-placement games from Uwe Rosenberg. It also feels more straightforward and focused.

I’m not a board game designer, and I don’t intend to become one. For anyone who plans to design a game, though, I recommend the streamlining approach. Think of a game, a series, or a genre that you love. Try to strip it down to its essence. Keep the parts that make it tick, and remove the ones that add extra components, setup time, or rules that you couldn’t explain to your dumbest co-worker. Such efforts help in both attracting the hobby to newcomers and decreasing the friction experienced by dedicated hobbyists.

Man, I sure do love Feast for Odin though.

But I agree with you. Too many games are bloated, especially if they began on kickstarter where a game whose design isn't even finished will announce four or five expansions if you go all in.

And part of my love for Feast for Odin is because most games are not Feast for Odin. Nor should they be! Though you now have me interested in Nusfjord even though I'm pretty sure I have all the Rosenberg games I'll ever need.

I'm with you on Ark Nova. My wife and a friend of ours love that game, but I think most of the game is actually a distraction from the game. For example, if you follow the theme of trying to make a cool zoo, you're going to lose. And most of the cards are geared towards making your zoo cool, but the only thing you actually need to pay attention to are the Scoring Cards. And while this is true of many games, I find that Ark Nova could probably have its systems cut in half, its play time reduced to an hour, and it would be much improved.

I've not read this yet but I am *very* interested - on my reading list. Thanks for the shoutout!!